This week the

International Technology, Education and Development Conference (INTED), took place in the wonderful city of Valencia, Spain. As you can see in the photos above, Valencia was a perfect choice of city to host this conference, because along with possessing strong respect and pride for the history and culture of the past, this city is looking to the future and is embracing technology. So, too, our challenge as educators is to respect our institutional history and academic achievements, but also to look to the future of education and how technology is reshaping and redefining our mission. This conference presented a wonderful opportunity for educational collaboration across disciplines and geographic boundaries facilitated by the crucial role that technology is taking in reshaping research and education. This conference clarified the realization that technological advancements, regardless of the field of study, edify all fields. For example, the use of interactive texts in mathematics or the drawing and then digital mapping of novels, using software that explores the depth of meaning through syntax and word repetition, all offer transferable ideas to explore other disciplines. Further, many presentations offered the development and findings in studying platforms for capturing, organizing and archiving work that will be increasingly housed in cyberspace rather than libraries. The other obvious enormous benefit of current technology, which was underscored at INTED, is how sharing research globally has become very easy. Minds that never would have been able to collaborate because of language and distance are now forming

communities of practice.

At INTED I was honored to present a paper on studio learning and teaching, which has been my passion. This passion arose from teaching studio art and art history and from studying the student centric Reggio Emilia inspired teaching at

School within School studio in Washington, DC. Studio learning is, as witnessed by anyone who has taken an art class, transparent and ongoing. Because of technology my passion has expanded to include studios that use technology, such as

Technology Enabled Active Learning (TEAL) at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, rather than art materials as tools for teaching and learning. In the same way that learning in an art class channels creativity to produce varied outcomes exhibiting the same content knowledge, so too can the thoughtful use of technology. I look forward to continued collaboration with the colleagues I met at INTED and to broaden the circle to those reached via the net. I share with all of you the paper I presented at INTED,

A Multi-case Study of Two Studio Learning Environments: Technology Enabled Active Learning (TEAL) at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a Reggio Emilia Studio at School within School (SWS) and appreciate all feedback, ideas and comments that will continue to illuminate this work. Through the thoughtful use of technology we can work together to create an egalitarian education for all.

MULTI-CASE STUDY OF TWO STUDIO LEARNING ENVIRONMENTS: TECHNOLOGY ENABLED ACTIVE LEARNING (TEAL) AT MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AND A REGGIO EMILIA STUDIO AT SCHOOL WITHIN SCHOOL (SWS)

Christine Morano Magee, Ed.D.

The George Washington University (United States)

Presented at The International Education and Development Conference (INTED) 2011

All rights reserved

Abstract

The classroom environment plays an important role in a student’s education, impacting student achievement and engagement in the process of learning ([1] Gandini, 1998; [2] Lackney, 1997; [3] Van Note Chism & Bickford, 2003). Technology should be seamlessly embedded into the learning environment in a way that serves all learners. The arts-based studio offers a platform for such integration, as both technology and art offer hands-on active learning.

This paper reports on a blended theory model resulting from a six month qualitative research study of two studio classrooms which span age groups and disciplines: the Technology Enabled Active Learning (TEAL) freshmen studio physics classroom at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a Reggio Emilia inspired atelier of School within School (SWS) Preschool on Capitol Hill in Washington DC. Data collection included non-participant observation field notes, interviews, photographs and artifacts. The study resulted in rich description of the structures and processes inherent in each studio and their implications for learning. The blended model depicts a studio in which technology, hands-on arts-based learning and a caring ethos, in concert, create an egalitarian holistic learning environment for all students.

The theoretical lens for this blended model includes, the Theory of Multiple Intelligences ([4] Gardner, 1993), the Ethic of Care [5], Universal Design for Learning [6] and Studio Habits of Mind ([7] Hetland, Winner, Veenema & Sheridan, 2007). This research paper is foundational, adding to the body of literature on the use of technology and arts-based learning in studio settings as a platform for further research.

This research concludes that a blend of technology and arts-based learning in a studio setting, (a) offers student-driven hands-on active learning, (b) breaks down barriers between teachers and students, (c) is conducive to the development of caring peer relationships, (d) removes hierarchy and competition, (e) empowers students towards proficiency in the use of tools for learning, (f) offers a platform for differentiated instruction using multiple modalities for teaching and learning, (g) provides embedded ongoing feedback and assessment and (h) facilitates learning that is transparent and open-ended. This model shows promise for the creation of egalitarian, inclusive, technology rich classrooms where methods and modalities actively engage learners.

INTRODUCTION:

There has always been much debate about the value of art vs. science. Nowhere has this debate been more visible than in the educational arena. There is an emphasis on the importance of math and science achievement as crucial to the global economy, while the current economic downturn has negatively impacted funding for the arts [8] (Madden, 2009). Scholars in the field of art education report that many research studies have attempted to correlate studying the arts with improved academic achievement, generating results which are void of a strong link between the two [9], [10]. (Eisner, 2002, Adams, 2008)). These studies are looking at the arts as a means for improving conventional measures of achievement rather than a broader model for learning [11] (Eccles & Elster, 2005). A potential strong benefit of the arts can be attained in the studio environment, which provides students an avenue to connect outside information with internal thought through active physical and mental engagement within a social environment [12] (Karkou, Glasman, 2004). There is also a school of thought which calls for new educational pathways that integrate the humanities and the sciences and sees this as an essential component for the survival of civilization [13], [14] (Bugliarello, 2002, Rosenzweig, 2001). The studio model of hands-on active-learning has been adopted for teaching physics at the college level ([15] Dori & Belcher; [16] Beichner).

Both the Reggio Emilia Pre-school Studio Model classroom and the TEAL Freshman Physics Studio at MIT have dismantled the concept of the traditional classroom. Each model has created a studio learning environment which contends that students are learning collaboratively and interacting with educational materials which allow for exchange of knowledge in multi-modalities. The philosophy underlying both models creates thoughtfully designed learning spaces supportive of the planned educational projects to be executed. These studio models allow for flexibility and innovation while the process of learning is taking place ( [17], [18] Ceppi, & Zini, 1998; Dori & Belcher, 2005). The classroom arrangement and materials for learning are strategically and purposefully placed in the room with the intent of creating an optimal learning environment [19], (Gandini, 2005). Reggio Emilia pre-school theory includes the concept, that in concert with parents and teachers, the environment is the third teacher [20], [21] (Edwards, Gandini & Forman, 1998; Gandini, Hill, Cadwell & Schwall, 2004). The environment of a Reggio Emilia school is not static; rather it is a continual reflection of active student learning [17], [22] (Ceppi, & Zini, 1998; Strong-Wilson & Ellis, 2007).

The potential significance of a multi-case study of these theories in action, will lead to emergent structures and processes, which will add to the body of academic literature on classroom environments and how they influence pedagogy and learning. Further, a confluence of these theories may offer a construct of a holistic learning space and process which includes the technological tools and materials for learning inherent in MIT’s model, and the caring, exploratory environment of Reggio Emilia which connects each child with the broader global community. These models move away from the institutional factory model which informed early public education and are still evident in many public high schools today [23] (Leland & Kasten, 2002). Bentley [ 24] (1998) postulates that a “learning society” can be created through environments which encourage relationships and motivation to inquire about things in collaboration and independently. Both models observed hold promise in producing such environments as well as contributing to educational theory.

1.1. Theoretical Foundation and Conceptual Framework

The theoretical and conceptual framework for this study includes an understanding of the historical roots of our current school environment, which is based on the industrial factory model of education. This model informed public education during the industrial revolution by creating schools, which mimicked factories and whose remnants still influence classrooms today [25] (Katz, 1987). Reggio Emilia views school as a place where learning is constructed both by individual learners and in collaboration with others [17] (Ceppi & Zini, 1998). TEAL has its roots in constructivist theory advancing that learning does not take place unless meaning is constructed by the student while being actively engaged in the process of learning [16] (Dori & Belcher, 2005).

The theories inherent in both the educational philosophies of TEAL and Reggio Emilia provided primary lenses to explore if these environments are examples of their underlying theories. Two key theoretical tenets of Reggio Emilia and Technology Enhance Active Learning were used as foundational lenses for the study of both models. Reggio Emilia states that the environment is the third teacher and the Technology Enabled Active Learning, TEAL, model advances that students’ learning is more successful in a collaborative, interactive technology rich environment. These theories combine to form a lens through which hermeneutics was used to study the Reggio Emilia atelier or studio classroom and the TEAL, Studio Physics Classroom at MIT. The concept of studying place as “landscape hermeneutics” led to a rich description. The literary “metaphor of landscape as text, the idea of inter-textual connections, multiple authorship, and the role of the reader in constructing meanings” all contributed to an interpretive landscape [26] (Armstrong, 2003, p. 9).

The “ethic of caring,” provided a lens through which to observe and understand the type of environment that studio offers [27] (Noddings, 2005). In order to view what is occurring in studio classrooms beyond literacy benchmarks, a broader definition of intelligence was employed through Howard Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences [4] (Gardner, 1993). Studio Habits of Mind, which codified visible ways of knowing and learning in studio, will provided a description of what occurs when a student engages in authentic learning in studio [7] (Hetland, Winner, Veenema, & Sheridan, 2007). The tenets of Universal Design for Learning (UDL), which advance fully accessible classrooms through the use of multi-modal assistive technology and accommodations, provided a further foundational lens through which to explore the inclusive nature of these models [28] (Rose & Myer, 2002).

1 METHODOLOGY

Because a study of an active classroom environment is a dynamic entity, which can be both unpredictable and fluid, some elasticity was built into the initial structure of the study. Maxwell’s [29] (2005) theory of qualitative research underpinned this study design. “Design in qualitative research is an ongoing process that involves tacking back and forth between the different components of the design, assessing the implication of goals, theories, research questions, methods, and validity threats for one another” [29 p. 3] (Maxwell, 2005, p. 3). The research model allowed for flexibility in order to capture elements of the case, which may not be obvious before the study commences [ 29] (Maxwell, 2005, p.3).

The selection of two models which have heterogeneous qualities of studio with a maximal variation between the cases found in comparing a successful early childhood model with a successful higher education model was further viewed by using the theories inherent in each of these models as facets of the theoretical lens with the goal of a creating a holistic picture of what was occurring in each case.

This multi-case study observed two different classrooms, the Reggio Emilia inspired School within School (SWS) in Washington, DC, and the Technology Enhanced Active Learning (TEAL) freshmen physics studio at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, for five one-week time periods over the course of one semester. The School within School (SWS) setting was observed Mondays through Fridays throughout the school day. The researcher also observed field trips, teachers’ meetings and other school events which added to a holistic picture of the studio classroom. Eighty-eight students from four classes, two pre-k and two kindergarten classes, were observed as they learned in the studio each week. These students were also observed in their classrooms and during school activities to document connections to the studio. The researcher conducted open-ended interviews with seven teachers; four of the teachers were founders of SWS twelve years ago. Also interviewed were the studio teacher or atelierista, the lead teacher, the music teacher and the four classroom teachers. Additionally four classroom aides were interviewed, all of whom were current or past parents of students who had attended SWS.

At MIT the researcher observed 213 undergraduate students in two sections of Physics Studio, TEAL, 113 students in Section A and 100 students in Section B. Thirty-four voluntary interviews with open-ended questions related to TEAL lasted between twenty minutes and eighty minutes. Twenty-two students participated, 10 from TEAL Class Section A, and 12 from TEAL Section B. There was a random disbursement of 12 female students and 10 male students. Four professors volunteered to be interviewed; two of the professors were teaching the sections of TEAL being observed and two of the professors where instrumental in the planning and implementation of TEAL at MIT. Additionally the TEAL Program Coordinator and his assistant were interviewed. Two graduate teaching assistants, one male and one female, and four undergraduate assistants, one female freshman, two male freshmen and one male junior, were interviewed. Data was collected during each site visit through observation, field journal notes, digital photography, artifacts in the form of student work and informational materials about the programs, recorded interviews conducted with the instructors, teaching assistants and students. Interviews were used to acquire background information not available through observation and also served as a reliability check for what was observed. Analysis and data collection occurred simultaneously during fieldwork as well as after field work. Data was collected during the initial weeks of classes, at mid semester and at the end of the semester. All information was transcribed and coded, to initially deconstruct or take apart the information [30] (Strauss & Corbin, 1987). Information was placed in analysis categories, “organizational”, and “substantive” to find emerging patterns, issues and themes [29] (Maxwell, 2005). Information was triangulated within each setting and then merged between cases and again triangulated. The results were then studied for emerging joint theory and the creation of a blended model. Outside readers were used as auditors to check for biases. The study resulted in a rich descriptive narrative of each case, and a foundational theoretical model, which resulted from a combining of the two cases.

2 RESULTS

The results of the case studies of SWS and TEAL studio classrooms were found through data collection which led to rich narratives that offered a confluence of observations, artifacts and the stories of those who interacted within these spaces. Despite the difference in educational levels, the Reggio Emilia inspired pre-school studio environment at SWS and the Technology Enhanced Active Learning (TEAL) freshmen Physics studio at MIT had many things in common. They both offered hands-on active learning experiences and used multi-modalities of teaching and learning to reach all students. Because of the hands-on nature of learning in the studio the teacher role shifts from being solely a lecturer to being a guide. Students worked individually and collaboratively to explore and experiment, using trial and error while actively applying information. There were also differences between the two studio classrooms. The researcher has purposefully chosen to illuminate the differences in these two studio classrooms results in order to bridge these gaps within a blended model. The major differences between these two studios were evident in two distinct area, nurturing and technology.

Because SWS studio is in a pre-school setting, there was a strong emphasis on nurturing, caring and development of the individual while simultaneously the student learned to work, to cooperate with and to communicate with others. There was little technology in the pre-school studio, which was arts-based. In the MIT TEAL studio there was a less nurturing environment consistent with college aged students. State of the art technology was seamlessly embedded into the classroom to aid in both teaching and learning. The following vignettes are examples of the results found in this study of the nurturing at SWS and the use of Technology in MIT TEAL.

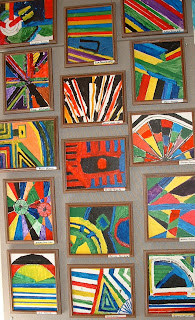

3.1 SWS The Individual is Nurtured and Celebrated:

Because of SWS’s belief that children create their own languages to express learning, and these languages are developed through creative expression, the studio was used as a spring board for collaboration with classroom teachers and the touch stone for ideas. These ideas and the development of creative languages by the students were facilitated by allowing multiple ways of knowing. The school employed a full-time studio teacher and also had a part-time music and part-time movement teacher. The studio and the classrooms were filled with visually stimulating objects, both man-made and natural. In this project-driven environment I observed students learning by doing. I also observed students using all of their senses to learn. All of the learning which occurred had an active hands-on component as a base. Each of these projects offered many different ways of knowing. The rich landscape of studio at SWS emerged as a philosophy through the four major emergent themes (a) student-centered learning, (b) community, (c) multiple ways of knowing, (d) comfort and care.

During my time at SWS, stories emerged as a key element in student-centered learning. Multi-modalities were used to accommodate all types of learners. Children were encouraged to compose and tell stories, act out stories through dramatic play, create art work that was reflective of their stories. Storytelling gave each child a personal voice and allowed them to relate their individual interests, memories, concerns, and priorities. Their stories demonstrated their individuality and gave the teachers a deep insight into what a child was thinking about, allowing them to express their thoughts through a variety of media.

Over the five weeks of observation at SWS the students were learning about literature. They were taught the difference between fiction, fantasy “a pretend story” and non-fiction “a story about a real person, place or thing.” Concurrently with the study of literary genres the students were also learning about Pueblo culture, art and also were discovering what it means to have a voice as a writer and an individual. The studio teacher used Pueblo clay story-telling dolls, artifacts of the Pueblo culture, as a symbolic vehicle to teach through. Each child created their own story-telling doll and composed a story that they told through their doll. These young students were learning concepts and facts by doing. In the studio classroom students learned many skills as a by-product of the project-based approach to learning. Through this one project students acquired skills, concepts and knowledge about multiple things including: working with clay, art history through sculpture, structuring a story, self portraits, drawing as symbolic, dramatic play and Native American culture and traditions. At the heart of the project, students learned about themselves finding their own personal storytelling voice. The art teacher asked the children to think about who their story-teller would be in their own story, “whose voice will it be in and how will you show your story in symbolic pictures and tell your story through your storytelling doll.” Since many students were too young to write complete sentences, students drew their story using a storyboard and then dictated the story to the teacher. Within the studio classroom allowed for multiple things to occur at once. So while the children drew their stories the teacher was able to circulate the classroom and spend individual time with each student, listening and transcribing those stories.

At SWS, the studio structure encouraged the children to be engaged in active learning, while permitting the teacher to spend quality individual time with each student. A unique feature of learning through studio methods was that, although all students were learning the same information, they were able to acquire the information in their own unique way and at their own pace. Once the teacher taught the students how to use the materials, they were free to be creative with them. There was a uniform outcome in the knowledge gained but each individual was able to demonstrate their learning in a creative and individual manner. The children were all treated as individuals and were excited when this project culminated with each child sharing their story with the entire class. Students appeared to be engaged and interested in learning about their classmates. At SWS the rich studio environment for learning was rooted in the arts and resulted in tangible products of that learning. Assessment of learning in the studio was therefore transparent and ongoing, providing the teacher with numerous student-created artifacts and an opportunity to observe progression in each student’s learning. The arts-based studio model at SWS revealed each child’s learning style preference and their individual talents.

Rather than just a process or a method of learning and teaching, studio emerged as a way of thinking. The SWS studio empowered students to be active participants in learning and in the community. The studio was boundless, and allowed learning to be open-ended and reach far beyond the walls of the studio.

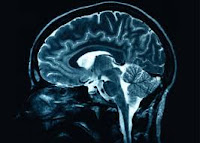

3.2 TEAL at Massachusetts Institute of Technology: A Technology Driven Studio Classroom

At MIT in the TEAL freshmen physics studio I encountered similar themes to those at School within a School studio but these themes were rooted in technology rather than art. A defining factor in the TEAL studio was the use of a rich assortment of technology available to the students, professors and teaching assistants. The classroom’s physical arrangement, the seamlessly embedded technology and the studio teaching and learning methods all contributed to the efficacy of learning in the TEAL classroom. I observed technology being used in multiple ways in the TEAL classroom: as a teaching tool, as a resource for learning, as a communication enhancer and as a way for students to interact as a class. Within the TEAL studio classroom the infrastructure of technology wove a web of support for both teaching and learning. The list of technology and technology based tools used in TEAL included: computers, online interactive text books, PowerPoints, available online and in class, assignments available online, visual applets of concepts developed for the class, desk top experiments with computer-based components, student personal hand held response systems, wireless microphones, audio surround sound, video cameras and video projection. Technology also offered multiple safety nets, letting the professor know the progress of the student groups as well as the progress of individual students; it allowed students, professors and teaching assistants to be alert to students who were in need of help. The technology, used to collect and track how individual students were progressing in class, provided a valuable tool for teachers to assess their own efficacy and a platform for ongoing research into the efficacy of TEAL as a model.

The TEAL studio is set up both physically and philosophically to use multiple learning tools simultaneously, allowing simultaneous interaction among students, professors and teaching assistants. Despite having over one hundred students in the class the TEAL studio was able to create a small class atmosphere, which lead to collaborative practice. This was accomplished by seating students at round tables in teams of nine, and subdivided into groups of three. Each group of three shared a computer. During each class, I observed that students worked as individuals, taking notes during the brief initial presentation of material to be covered that day and then worked in teams of three on computer-driven desk-top experiments. Finally they worked in their team of nine to solve mathematical equations that were the language of the physics concepts they were learning. Students formed pro-social relationships with this group of peers. TEAL also gave students the opportunity to respond to problems individually through the electronic personal response system, allowing the individual to be recognized with the aid of this technology. One student reflected upon the multi-modal nature of TEAL: On each screen, so we can see what he [the professor] is doing, they keep a PowerPoint up on half of the screens and video, him solving problems on the board on alternate screens. Sometimes there are three things shown around the room at once. I can hear the professor talk (because he is wearing a wireless microphone) and see what he is writing (because he/she is being filmed and projected on large screens around the room). Actually I prefer (viewing the professor) on the screen because I can see everything going on.” The professor is free to walk around the room and interact with the students throughout the class.

The TEAL studio used technology to extend beyond its physical walls into a virtual space. Students used computers outside of class as access points to TEAL, with twenty four hour access to the online interactive text book, online help, and PowerPoints. All course materials were are available online from the first day of class. The students therefore knew what was expected of them and were able to schedule their time accordingly. Much of the technology used in the TEAL studio, such as computers, LCD and video projectors, and audio equipment provided consistent sensory accommodations to all the students. This technology on a smaller scale is commonplace in most schools.

The professors, teaching assistants and students agreed that one key to the successful functioning of the TEAL process is the Personal Response System (PRS). These small hand-held electronic devices enabled each student to input answers to multiple-choice questions which were introduced intermittently during class. This system provided the professor an “instant read” on what percentage of the class was grasping the concepts. There was also an interactive system, through networked desktop computers used to provide feedback to the professor and the entire class during desk top experiments. This further permitted the professor to know which group and individual students were struggling with particular concepts. A professor, who was instrumental in the development of TEAL at MIT, described the importance of the personal response system. “The most important technology is these clickers [the personal response system]. They enable us to ask questions and get them to respond. To get an idea of what is going on, how they are doing, anonymously.”

Every professor interviewed cited the importance of having this immediate feedback mechanism. “In the standard lecture format you can go through it and think you know everything and get to the problem set or exam and you realize you don’t know the concepts. With the concepts, PRS really helps.” In the TEAL studio the format and the classroom are integrated for a common goal. A professor described how the structure promoted active learning: “In lecture recitation you may have interaction with your students but TEAL is specific to the classroom setting. TEAL students are seated at a round table where they are facing each other and have three common computers with access to slides everywhere on the walls. There is a white board where they can do problems and then there are presentation screens where they can view slides. Students look at each other rather than at a central focal point. They also utilize the PRS which can create a so-called turning point as each student uses the little remote to answer anonymously. The students can click on their choice and the professor knows what the students know. If twenty five percent get it wrong I know I have to go back and go over the concepts again. “

Students did their group desk-top experiments in sub-groups of three, posting a series of answers as they worked through the hands-on experiments. Their answers submitted electronically registered on the large video screens around the room linked to the computer. If a group of student was not keeping up with the rest of the class or were having difficulty in getting the correct solutions the professor or teaching assistant could look at the screen and go over and assist the group instantly.

Views on collaboration within the TEAL classroom often focused on the ability of students to relate to the world around them. Understanding that technology has promoted a diminution in boundaries and increased the ease of communication, highlights the importance of developing an awareness of a smaller, more immediate and vastly more diverse world. One professor underscored this point. I don’t care if they remember Maxwell’s equation. They are MIT students- they will remember that. All the technology in TEAL is geared toward getting them to learn to communicate with each other and get them engaged in class. In this environment you are teaching yourself, but we also provide a platform in which you are also teaching others.” A majority of the students, staff and faculty that were interviewed agreed that the technology provided a rich platform for teaching, learning and collaboration.

3 CONCLUSION

The differences between the two studios, with the SWS pre-school focusing on nurturing and the MIT’s TEAL college studio focusing on using technology could be attributed to the differing educational level. This research concludes that a blend of technology and arts-based learning in a studio setting, (a) offers student-driven hands-on active learning, (b) breaks down barriers between teachers and students, (c) is conducive to the development of caring peer relationships, (d) removes hierarchy and competition, (e) empowers students towards proficiency in the use of tools for learning, (f) offers a platform for differentiated instruction using multiple modalities for teaching and learning, (g) provides embedded ongoing feedback and assessment and (h) facilitates learning that is transparent and open-ended.

4.1 SWS Studio: An Emergent Definition

What began as a study of a particular room, the studio classroom at SWS, led to a study of the entire school and the realization that the SWS studio was synonymous with education. Studio proved to be both a physical place and a comprehensive philosophy. The result of the SWS case study suggests that the studio environment is in many ways a state of being. The studio concept, evidenced by project-based learning at SWS, revealed the following conclusions: that students approached all learning as if it was a creative project, the teacher acted as a guide, that tools and materials were visible, that competence in using these materials is taught and that students were comfortable and free to create varied rather than uniform products. Further, SWS took the idea of studio learning in an elegantly crafted transparent direction between the classroom, the studio and the community. What is truly unique about this definition of studio is that one can conclude, that it is both a cerebral space and a physical space, it is a way of looking at the world as a studio to be explored and everything in it is a potential creative tool or material. This emergent definition of studio at SWS is congruous with the research on studio environments advancing that learning in studio is both individual and collaborative [31] (Carbone, Lynch, Arnott and Jamieson, 2001; [7] Hetland, Winner, Veenema, and Sheridan, 2007; [33] Stevens, 2002). Further, the concept of studio as being boundless is supported by the tenets of Reggio Emilia theory which advances that the physical studio is the hub for the initiation of ideas which reach out into the world [19].

4.2 Technology was a driving force in TEAL

In recent years a growing body of research discusses the efficacy of integrated technology in the classroom and how it may affect student achievement ([33] Lei & Zhao, 2007; Rose, Meyer, & Hitchcock, 2006; [6]] Sheffield, 2007[34]). New ways to use technology to serve “students in the margins” [6] (Rose, Meyer, & Hitchcock, 2005, p. 30) is seen as key to developing a truly universally designed inclusive classroom. A defining factor of learning in the TEAL studio was the use of a rich assortment of technology, available to the students, professors and teaching assistants. The introduction of technology was integrated into the course materials, not displacing the use of traditional print media but rather enhancing it. Students and teachers became proficient in the use of technology in order to operate in the TEAL classroom. This was accomplished with the use of interactive textbooks and other supporting materials which address the needs of different types of learners. MIT’s use of media is supported by the principles advanced in UDL that “new electronic media offers the opportunity…the obligation to reexamine old assumptions about teaching media and tools and reconsider their impact on learners” [28] (Rose, & Meyer 2002). TEAL was developed in such a way as to offer a full complement of technology-driven learning tools suitable for a variety of learning styles. The theoretical importance of understanding and using tools, to “stretch and explore” learning, an important tenet of the studio thinking frameworks, was supported by the TEAL studio approach ([35] Hetland, & Winner, 2005). Students and teachers had to become proficient in the use of technology in order to learn in the TEAL classroom, with its use of technology as a link to expanded teaching and learning and as a tool for communication. The students and the professor agreed that the PRS System was very useful technology since it instantaneously gauged students’ understanding of the material being covered. The dependence on technology had both positive and negative implications. A studio classroom that is enriched by technology demands significant maintenance, training of teachers and students to be proficient in the use of this technology and an investment of time for planning and curriculum coordination.

4.3 Implications for Practice

Technology in the studio classroom serves the following major functions: it enhances communication among students, professors and teaching assistants, it allows for communication and information in and outside of the studio, it provides hands-on collaborative opportunities for students to apply their knowledge and it provides accessibility enhancements of the professors’ communication and digital text and graphics, microphones, video cameras and computers. The rich technological environment of TEAL demanded two full-time, dedicated technical staff members who were not only well versed in the use and maintenance of the technology but also had degrees in physics, the subject being taught. The use of technology in the studio setting implied that practitioners must look forward to how technology impacts

teaching and learning by creating new ways of knowing. Technology changes the teacher’s role to guide and adds a new layer of scaffolding to instruction, assessment and learning. The capabilities of classroom computers should be explored to reach maximum advantage of use. The use of technology in the studio classroom allowed students, professors and teaching assistants to communicate in class and out of class. The personal response system which gave students a chance to instantaneously respond to question giving the professor an ongoing means of assessing student understanding was described as one of the most positive uses of technology for teaching and learning in TEAL. The use of technology integrated into

instruction and application of knowledge requires training of both teachers and students in the use of the technology. It also requires thoughtful, purposeful opportunities for students to use the technology to problem solve, think actively and make direct correlations to the subject being studied ([32] Sheffield, 2007). Research shows that it is not the quantity of the technology used in a classroom but rather the quality of the technology and that positively effects student achievement ([31] Lei & Zhao, 2007). Integrating and embedding technology into the classroom therefore is challenging but once achieved, may provide a seamless way of introducing accommodations for learning to all students.

A confluence of the results of the two case studies of studio classrooms leads to the conclusion that the studio as classroom is conducive to student-driven hands-on learning. Technology, both hardware and software, is seamlessly embedded into the classroom providing tools both for teaching and learning. Studio moves away from the lecture/recitation format enabling the teacher and students to interact throughout the class. Because of this ongoing interaction, the studio classroom model may break down the barriers among teacher and students in the classroom and may allow caring peer relationships, and teacher-student relationships to occur. These caring reciprocal relationships in the studio may occur by the removal of hierarchy and competition in the classroom. This is achieved through the teacher acting as a guide, empowering each student by making sure they are proficient in the use of the technology, which are the tools for learning, and then facilitating the acquisition of knowledge. Because learning is occurring by students actively applying knowledge, there is a transparency inherent in the studio classroom. The teacher is able to observe students while they are exploring information, gaining and applying knowledge. This allows the teacher to assess student understanding and offers both the teacher and the student the opportunity to understand and recognize how each student learns. Rather than only judging a student through summative evaluations, the studio classroom offers constant interactions and opportunities for formative assessment and reflection. This, in turn, allows the teacher to help the student to direct their own learning. Students are aware of what they do not understand when they are actively involved in attempting to apply knowledge. SWS embracing of the Reggio Emilia’s tenet of encouragement of individualized learning which emerges from a student’s unique way of understandings, combined with MIT, TEAL’s use of technology to broaden ways of learning and assessing, may offer students with disabilities and those placed at risk opportunities for interaction with others and may lead to a self knowledge of how they learn. An overarching benefit of studio was the strong pro-social skills they produced through collaborative work and peer teaching and learning. This model shows promise for the creation of egalitarian, inclusive, technology rich classrooms where methods and modalities actively engage learners.

REFERENCES

[1] Gandini, L. (1998). Educational and caring spaces. In C. Edwards, L. Gandini & G.Forman (Eds.), The hundred languages of children (2nd ed.) (pp. 161-178).Westport, CN: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

[2] Lackney, J. A. (1997). The overlooked half of a large whole: The role of environmental quality management in supporting the educational environment. Paper presented at the Second International Conference: Buildings and the Environment, Paris, June 9-12, 1997.

[3] Van Note Chism, N., & Bickford, D. J. (2002). Improving the environment for learning: an expanded agenda. In N. Van Note Chism & D. J. Bickford (Eds.), The importance of physical space in creating supportive learning environments (pp.91-97). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

[4] Gardner, H. (1993). Frames of mind, theory of multiple intelligence. (10th anniversary edition). New York: Basic Books.

[5] Noddings, N. (2003). Caring: a feminine approach to ethics and moral education. (2nd Edition). Berkeley: University of California Press.

[6] Rose, D. H., Meyer, A. & Hitchcock, C. (2005). The universally designed classroom: Accessible curriculum and digital technologies. Cambridge: MA: Harvard Education Press.

[7] Hetland, L., Winner, E., Veenema, S, & Sheridan, K. (2007). Studio thinking: The real benefits of visual arts education. New York: Teacher’s College Press.

[8] Madden, C. (2009). Global financial crisis and recession: Impact on the arts’, D’Art Topics in Arts Policy, No. 37, International Federation of Arts Councils and Culture Agencies, Sydney.

[9] Adams, K. (2008). The relationship between art education and student achievement in elementary schools. Doctoral thesis. Minneapolis: Walden University.

[10] Eisner, E., (2002). The arts and the creation of mind. New Haven: Yale University Press.

[11] Eccles, K, Elster, A.(2005). Learning through the arts: A new school of thought?. Canadian Education Association, 45(3) 45.

[12] Karkou, V. , Glasman, J. (2004). Arts, education and society: the role of the arts in promoting the emotional well-being and social inclusion of young people. Support for Learning: British Journal of Learning Support, 19(2) 57-65.

[13] Bugliarello, (2003). A new trivium and quadrivium. Bulletin of Science Technology 23(2), 106-113.

[14] Rosenzweig, R. (2001). Course Changes for the Research University,” Science, Vol. 294, October 19, 2001, pp. 572-28.

[15] Beichner, R. J. () Introduction to the SCALE-UP Student-Centered Activities for Large Enrolment Undergraduate Programs. Invention and Impact: Building Excellence in Undergraduate Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) Education National Science Foundation (NSF) Division of Undergraduate Education (DUE) In Collaboration With the Education and Human Resources Programs (EHR) American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) 61-66.

[16] Dori, Y. J., & Belcher, J. (2005). How does technology-enabled active learning affect undergraduate students’ understanding of electromagnetism concepts? The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 14, 243-279.

[17] Ceppi, G., & Zini, M. E. (1998). Children, spaces, relations: Metaproject for a environment for young children. (L. Marrow, Trans.). (3rd ed.). Reggio Emilia Italy: Reggio Children Domas Academy Research Center.

[18] Dori, Belcher 2005 Dori, Y. J., Belcher, J., Bessette, M, Danziger, M., McKinney, A., & Hult, E., (2003). Technology for Active Learning, Materials Today, 6(12), 44-49.

[19] Gandini, L., Gandini, L., 2004. Foundations of the Reggio Emilia Approach. In J. Hendrick (Ed.), Next stepstoward teaching the Reggio way: Accepting the challenge to change (2nd ed., 13-26). Upper SaddleRiver, NJ: Pearson/Merrill/Prentice Hall

[20] Edwards, C., Gandini, L., Forman, G. (Eds.) (1998). The hundred languages of children: the Reggio Emilia approach to early childhood education.(2nd Ed.) Greenwich, CT: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

[21] Gandini, Hill, Cadwell & Schwall, (2004). Gandini, L., Hill, L., Cadwell & Schwall, C. (Eds.). (2005). In the spirit of the studio: Learning from the atelier of reggio emilia. New York: Teachers College Press

[22] Strong-Wilson & Ellis, Strong-Wilson, T. & Ellis, J. (2007). Children and place: Reggio Emilia's environment as a third teacher. Theory Into Practice, 46, 40-47. 2007

[23] Leland C. & Kasten W. (2002). Literacy education for the 21st century: It’s time to close the factory. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 18, 5-15.

[24] Bentley, T. (1998). Learning beyond the classroom. London: Routledge.

[25] Katz, M. (1987). Reconstructing American education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

[26] Armtrong. (2003).

[27] Noddings, N. (2005). The challenge to care in schools: an alternative approach to education. (Second Edition). New York: Teachers College Press.

[28] Rose, D., & Meyer, A. (2002). Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

[29] Maxwell, J. A. (2005). Qualitative Research Design: An interactive approach (applied social research methods series) (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

[30] Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Sage Publication.

[31] Carbone, A., Lynch, K., Arnott, D., & Jamieson, P. (2001). Introducing a studio-based learning environment into information technology. Paper presented at the Flexible Learning for a Flexible Society Meeting. Toowoomba, Queensland, Australia.

[32] Stevens, K. L. (2002). School as Studio: Learning through the Arts. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 39(1), 20-23.

[33] Lei, J & Zhao, Y. (2007). Technology uses and student achievement: a longitudinal study. Computers and Education, 9 (2) 284-296.

[34] Sheffield, A. (2007). Necessary variables for effective technology integration. Idaho: Boise State University.

[35] Hetland, L., & Winner, E. (2005). Arts and understanding: the studio thinking framework. Paper presented at the Harvard University Graduate School of Education Project Zero Classroom 2005: Views for Understanding|, Cambridge,MA.

Labels: Communities of Practice, Educational Technology, INTED, International Education, MIT, Reggio Emilia, School within School, Studio, Studio Teaching and Learning, Technology Enabled Active Learning.